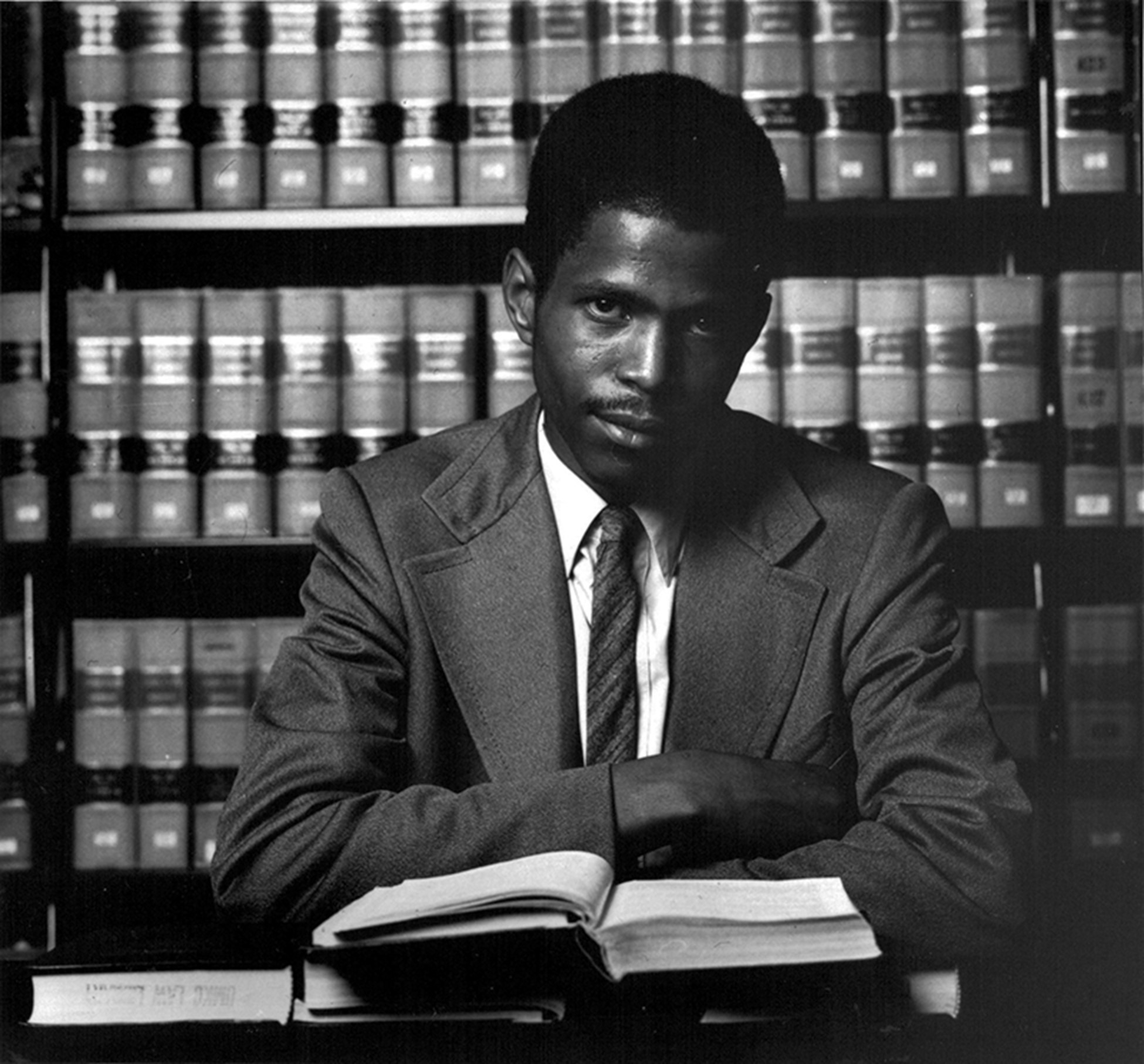

Alvin Sykes

1956-2021

Human rights activist Alvin Sykes devoted his life to helping those wronged by the U.S. justice system.

Sykes was raised in Kansas City’s east side community by his foster mother, Burnetta Page, who fed his insatiable curiosity through books, magazines, and music. Feeling that the neighborhood was unsafe for Alvin following civil unrest in 1968, Page sent him to Boys Town outside Omaha, Nebraska, a Catholic school for at-risk youth. He later attended Sumner High School in Kansas City, Kansas.

At 16, Sykes left school and spent his days at the Kansas City, Kansas, Public Library, a few blocks from his home at the time, studying books on music business, math, and eventually law. “I transferred to the public library,” he later joked. Sykes emerged a self-taught legal scholar and crusader who worked through the justice system on behalf of minorities and the poor.

In 1981, he sought justice for Steve Harvey, a Black musician who was beaten to death at Penn Valley Park in a racially motivated attack. When an all-white jury found the white assailant not guilty, Sykes formed the Steve Harvey Justice Campaign and convinced the U.S. Department of Justice that Harvey’s civil rights had been violated. The case was tried in U.S. District Court, where Harvey’s killer was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Raised Catholic, Sykes converted to Buddhism at 18. Musician Herbie Hancock, who became his friend and spiritual mentor, had introduced him to the religion. In Buddhism Sykes found a search for existential truth that mirrored his pursuit for justice in the legal system.

Sykes rose to national prominence in the early 2000s when he took up the Emmett Till case. In 1955 Till, a 14-year-old Chicagoan, allegedly whistled at a white woman while visiting his cousin in Mississippi. He was later abducted at his cousin’s home by two white men and then beaten and murdered. Both killers were acquitted by an all-male, all-white jury. Six decades later, Sykes successfully lobbied for the creation of the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act. The Till Bill, as it was known, provided funding to reopen investigations of racially motivated homicides committed during the civil rights era.

A lifelong learner, Sykes referred to libraries as “the great equalizer.” In 2013, the Kansas City Public Library named him its first Scholar in Residence. He remained a presence at the library and continued his tireless crusade for justice until his death in 2021.